In the “How Engaged Are You?” experiment I conducted three trials where I manipulated the environment in which participants viewed the poem, “Save Her Yellow Wishes,” and a complimenting interactive art piece. Here are my conclusions and overall thoughts about the data that was collected.

Before continuing please feel free to read the poem, “Save Her Yellow wishes,” by clicking on the “Poems” tab and finding the poem there. Or take the survey available by clicking on the “How Engaged Are You? -Survey” tab.

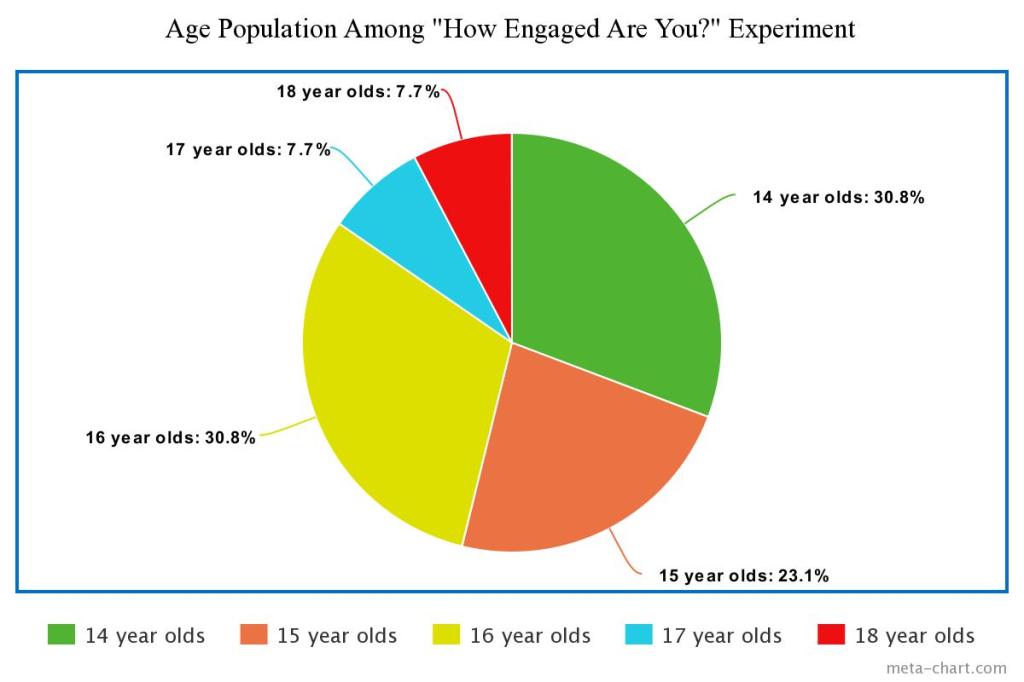

In this experiment I asked the same eight questions to the participants. A few of these questions included what their age was, what emotions they thought the interactive piece gave off before listening or reading the poem, what imagery they saw “come to life” with the interactive piece and poem together and lastly, how engaged they were throughout the experience on a scale 1-10. The pool of participants consisted of high school students ranging from the ages 14-18 years old.

As mentioned before, this experimented consisted of three different trials where I manipulated the situation in which the audience received the subject. Here is how each of them were conducted:

Trial One: Digital Survey

In this trial I made a google form that I sent out to a select group of students where they saw the interactive art piece through digital photos and videos and read the poem through clicking on a link that was provided. The point of this trial was for the participants to have no emotional connection with me as the author of the pieces they were reading and answering questions about. I let the participants complete the form on their own and gave them an open time frame of when they could submit the questions into me. This survey is available for anyone to take that can be found under the “How Engaged Are You?-Survey” tab.

Trial Two: A One-On-One Conversation

For this second trial I met with participants one-on-one in a private room. I informed them that I will be reading the poem out loud to them that would be complimented by the art pieces in front of them. Before I read the poem to them, I asked them what emotions the art piece gave off. Once they responded I read the poem out loud to them and interacted with the art piece. After the poem was over, I asked them the same questions that the participants from the first trial answered. I asked these questions out loud and they verbally gave me their responses as I wrote them down. I set this trial up to be a conversation between the audience member and myself, the author, to build that connection of emotion that the poem gave off.

Trial Three: Audience Setting

Lastly in this third trial, I gathered all the participants who took part in this trial as a group. I handed out a questionnaire and asked them to answer the questions after I had read the poem. Then I read the poem out loud to the group while interacting with the art piece, after it was finished they wrote their responses on the questionnaire and handed them into me when finished. I put the participants in this group setting to simulate how it might be if they were to go to a museum and listened to a poet reading one of their poems that was complimented by a physical piece of art.

Results & Graphs

Before I conducted any of these trials I hypothesized that the participants who took part in trial two would be the most engaged because of the connection that would be built through the conversation we had. I felt that without the potential pressure from peers being around them while they answered the questions that they would be more open about their responses.

All of the participants who were apart of this experiment were asked how engaged they were on a scale 1-10, 10 being very engaged and 1 being the least engaged. After some calculations here are some averages that I have concluded: participants’ engagement levels from trial two averaged out to be an 8.1 while participants from trials one and three came out to be lower. Trial one’s engagement levels averaged out to be 6.75 and trial three’s engagement levels averaged out to be a 7.5. From these calculations it has proved that my hypothesis for this experiment was correct.

Although some trials showed to be more engaged than others, the participants overall enjoyed the whole experience. Down below you can see a pie chart showing the common words that were used to describe the interactive art piece before the participants read/listened to the poem. Almost half of the participants descried the art piece to be happy and calm while others did see a stressful and sad aspect of the piece. See the chart further down to see how the participants described the art piece and poem together as whole.

A vast majority of the responses I received followed a pattern with each other. The audience interpreted the poem and art piece in their own unique way but all had the common ground of having a grasp of what the poem is truly about.

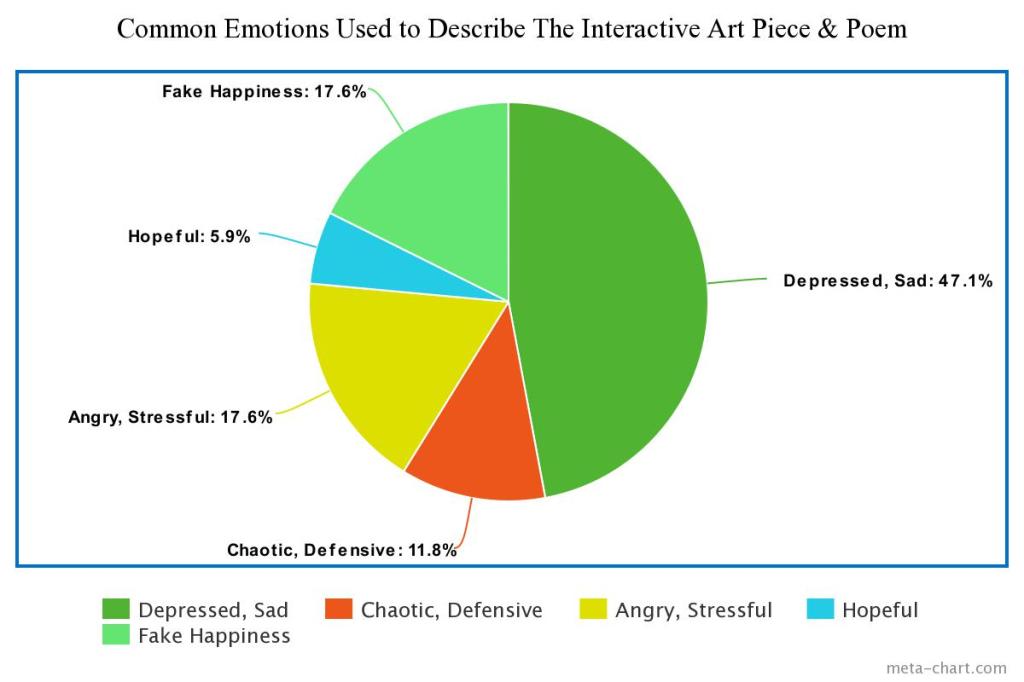

Below you will see another pie chart that displays the common emotions used to describe the interactive art piece and poem by the participants after they listened to/read the poem. As you can see almost half of the participants described the art piece and poem together to be sad and/or depressive. You can see that the percentage of feeling angry or stressed has increased by 5.8 precent. An emotion described as “fake happiness” was also mentioned a lot among responses, the participants didn’t have an exact word for it and neither did I but collectively, we knew what that feeling was.

Responses & Quotes From Participants

When participants were asked the question, “What imagery comes to mind when you see the poem and interactive piece together? What imagery ‘comes to life?'” they had responses that connected the bottle of tears from the poem to the interactive piece as it was made up of three bottles that showed progression through the storyline of the poem. “The dandelions and water come to life, lights become more hectic representing chaos,” one participant explained it as. Participants across all of the trials connected the dandelions from the poem into the physical piece and expressed that they resembled wishes the girl was making as she was dealing with emotional stress.

When one particular participant was asked the question, “How does the interactive art piece compliment the poem?” they responded with, “The lights represent her breaking down, how she is doing and when she is finally breaking.” Most of the participants expressed that the bottles in the interactive art piece told the metaphorical storyline the poem had and that it especially showed growth and progression of the girl in the poem.

Lastly I would like to discuss the responses I collected when participants were asked the question, “What do you think the piece, ‘Save Her Yellow Wishes’ alone is about? How do you interpret it?” Like I said above, the participants interpreted the poem in their own unique way but they all got the same grasp of the poem, even across all of the trials. “I think it is about a hopeful girl who feels beneath her peers. Her feelings of being small and insignificant help her see the beauty in small things such as dandelions. However, the small things are simply enough to distract her from her emotional pain.” says a participant who took part in the first trial. This participant specifically grasped onto the font size changing and was the only one who was able to notice it that connected it to the full meaning of the poem. Other participants describe the poem to be about “hiding emotions,” or “faking real happiness,” which are all correct because that is the main focus of the poem that I intended it to have.

In summary, we can say that no matter how you read a poem whether its online, in a book, printed out on a sheet of paper, verbally read to you, the audience is bound to interpret it in its intended way. Although perhaps the environment or method they are receiving the poem maybe influence the full idea, my experiment has proven that all of the participants had a good grasp on the overall meaning of the poem, “Save Her Yellow Wishes,” and were engaged in the activity.